“He really did have super ears, you know”, says Natalie O’Neill of Halcro. In an early white paper, the company’s founder Dr Bruce Candy, middle name Halcro, claimed to “have very unusual ears; I can hear up to 23kHz in one ear and 21 kHz in the other”. At the time of the first coming of Halcro in the 1990s, Candy made claims with more front than a bullfighter in a Hemingway novel. Yet, Stereophile rewarded those ears by dubbing its October 2003 cover star, the inaugural Halcro dm58 monoblock power amplifier: “The Best Amplifier Ever”. To date, no other product has graced its cover with this ‘best ever’ proclamation. Exponential success then followed these unconventional amplifiers which boasted freakishly low “parts per billion at full power” levels of distortion. The original ‘dm’ units remain a coveted cult product today, long after the original company was sold by Candy and Halcro disappeared as rapidly as it came.

Candy certainly covered some territory. He was born in South Africa and is an alumnus of Cambridge University in maths and physics. He settled ultimately in the late 1980s in Adelaide, the Australian city of churches and bizarre murders, to strike gold literally with the world-famous Minelab hand-held metal detector company. The region’s geological conditions, perfect for fruit and wine growing, were perfect also for developing a device that could find its target object through mineral-rich soils faster and deeper than any other in the marketplace. Candy brought this novel technological discipline derived from his work on microwave and ultrasonic technology for Minelab across to the design of these unique “Super Fidelity” audio amplifiers with revelatory, some say revolutionary, results.

“The Longwoods”: Mike Kirkham, Peter Foster & Lance Hewitt

“The Longwoods”: Mike Kirkham, Peter Foster & Lance Hewitt

O’Neill, the company’s bookkeeper, bore witness to the maiden Halcro amplifier Candy and his brother-in-arms Lance Hewitt worked up in “Garageland” across two milk crates. The new owners of the company call her “a Halcro tragic”. When Halcro was resurrected by its former lead engineer Lance Hewitt, with fellow Adelaideans Dr Peter Foster and Mike Kirkham (as Longwood Audio), she returned to the fold in a vintage Halcro T-shirt without a moment’s hesitation. O’Neill is one of a privileged few who, like Philip Guttentag of Vivid Audio, own both stereo and monoblock versions of Halcro amplifiers. “Why?” I ask her. “Because I have good ears too”, she answers matter of factly.

In the Half-Between World – The Outer Bridge, Poem by Sun Ra

Candy was a passionate music lover with superior taste in Hi-Fi (those ears again). Notably, he had a penchant for Shure moving magnet cartridges, the regal EL34 valve and Partridge output transformers, the same brand used in early Hiwatt guitar amplifiers which, paradoxically, likely sent Pete Townshend deaf. Candy detested the harsh sound of early transistor amplifiers. But, equally, he detested any and every kind of distortion which would result in any kind of deviation from the original input signal. He converted to power FETs in the output stage, specifically vertical FETs commonplace in microwave switching technology, only when he was certain his amplifier design could reproduce, as he asserted of the original dm38 stereo model, “with better than 99.9997% purity of all tones across the entire audio range”. Candy argued that amplifier distortion generated false signals or ‘ghost tones’ that the human ear could detect and that his amplifier produced “less false IM or harmonic signal than the measured threshold of the human ear”.

In the ensuing brouhaha over how to measure immeasurably low levels of distortion (and their meaning) and the frenzied debate over patents and circuitry second-guessing, one of Candy’s psychoacoustic polemics seemed to get lost in the mix. “It is often assumed”, he ventured, “that if the distortion of a product is less than the measured noise, then it is necessarily inaudible. That is not necessarily so”. In the half-between world of signal-to-noise, Candy is suggesting it is possible for the human ear to detect things below the measurable noise floor in the muck and mire below surface level. And not just because of a lowering of that noise floor which, because of the complete lack of distortion in a Halcro amplifier, is having a profound but imperceptible effect on a listener’s perception of musical information above it. Many amplifiers these days are claiming distortion factors below “the threshold of hearing of the human ear”. Perhaps it’s things like this that still so clearly sets the Halcro apart, sonically speaking.

It took the El Padrino 10 years of R & D to bring his amplifier to market. It took Longwood Audio six years to bring it back. In that time, Mike Kirkham says they listened to a succession of prototypes without ever once measuring the results. Longwood Audio must have been wearing their collective underpants on the outside the day they decided to measure the final product. They were stunned to discover that the new Eclipse Stereo model measured significantly better, yet sounded significantly more musical, than the last Halcro flagship, the now mythical dm88 monoblock power amplifier.

One of Halcro’s evaluation and recording studios

One of Halcro’s evaluation and recording studios

Dwell they, the Sound-Scientists

I wonder whether the word “distortion” was ever banned for overuse in the Candy household. Such was his fanatical zeal to rid his circuit of it. Putting aside, for the moment, legitimate questions about the “purity” of the original input signal in the first place, the new Halcro Eclipse amplifier models, of course, preserve Candy’s distortion aversion tenets throughout. Even the standby switch on the new Halcro Eclipse Stereo power amplifier is air-pressure activated rather than a traditional electrical switch to minimise interference. Distortion of the audio signal during amplification can take many forms. A draft paper by the new Halcro crew (‘the Longwoods’) provides a taxonomy of but a few of its types: amplitude or volume distortion, frequency dependent distortion, phase or time delay distortion, crossover distortion, harmonic distortion, and intermodulation distortion responsible for generating those often ignored but jarring “ghost notes”. Each type is different, of course, and requires a different solution. Candy was sufficiently contumacious to seek to address all.

While the basic amplifier stages are “standard D. Self” in format, according to B. Candy in that early white paper manifesto: In order to achieve these ultra-low levels of distortion, all aspects of standard low distortion circuitry required considerable conceptual change; about 12 fundamental conceptual changes in all. Every stage of every circuit I have ever seen will increase distortion if swapped with the equivalent stage in the Halcro amps. Hence there is not even a small bit of Halcro circuitry that is at all similar to the conventional low distortion high quality circuits. It would definitely take the average amplifier designer quite some time to recognise the circuit as that of an amplifier if presented with no direct clue as to its purpose. I don’t think that any designer would guess that the parts list was that of an amplifier if seen in isolation.

To think it all started by getting high. Candy decided to subject distortion to Under Heavy Manners because, the way his super ears heard it, distortion/s most perniciously affected the high frequencies of audio reproduction resulting in harsh and unnatural sound as well as compromising dynamics and transient performance. It is apposite that the “worst dm68”, he says, was measured for top end THD as “a mere 600 parts per billion at 20kHz at full power, a frequency where most amplifiers exhibit very poor behaviour”.

To detail all the unique features of the Halcro Eclipse Stereo power amplifier design is well beyond the scope of this review and this reviewer’s addled brain. Compared to the average high quality amplifier design, this is just nuts. So consider what follows a micro-taxonomy of but a few key technical aspects. The updated Halcro website is a goldmine of information about the company and its auspicious history. One article, in particular, written by Isao Shibazaki of the legendary Japanese audio magazine MJ, on the earlier dm68 mono, is an exhaustive deconstruction of the sound-scientist’s dazzling originality. Even absent the invariably amazing Japanese photography, the article is guaranteed to give the inquisitive techno-freak a robot-sized chubby.

An enduring misnomer is that the Halcro amplifier applies gobs of globs of global negative feedback to minimise distortion. A trip down the techno-amazon of Candy’s patent applications, a heady experience in itself, reveals that our sound-scientist is not. Rather, following on from the pioneering work of designers like Malcolm Hawksford and Bob Cordell, he is using “error cancelling” not error lowering circuitry of conventional negative feedback designs, at key localised sites. Seems to this author, these localised distortion cancellation ‘nests’ are site-specific to specifically address the type of distortion there encountered. Put another way, Candy is applying different techniques of error cancellation circuitry at different sites to address different types of distortion, at different stages in the circuit. Where his patents go beyond his ‘feed-forward’ forbears is by introducing “floating power supplies” to, well, feed the localised error correction stages”. Far out. (The author pauses here for a gulp of his finest and most psychedelic bottle of Tasmanian single malt whisky). Correct me if I am wrong.

Candy, who could no doubt hear distortion artifacts in the crunch of his cornflakes over breakfast, felt that the real magic in his design was the output stage. His forensic decision to go with complementary (N-/P-channel) vertical FETs isn’t that radical given he was already a disciple of microwave switching technology. V-FETs are inherently fast in operation and switch on and off with the necessary complementary alacrity to eliminate crossover distortion. An intrinsic problem with their use, however, is keeping these output FETs stable in temperature so that each power FET draws the same current at the same time. The ingenious way Candy addresses the “unavoidable” potential for thermal distortion, is a prime example of his error-specific application of compensating circuitry.

It also exemplifies his patented use of floating power supply rails to ‘thermally track’ shifts in the ‘point in time’ performance of the power FETs to ensure the delicate things don’t get too ‘stressed out’ and remain constantly within their design envelope. Candy worked his corrective circuits “in such a way that they do not intrinsically affect parameters such as gain, bandwidth, phase transfer etc.”

The output stage is run in Class-A/B, close to Class-A. But the Halcro amplifier is not a fully complementary symmetrical circuit because this will be heard as only inharmonious odd-order harmonic distortion, “with zero contribution from even harmonics”. When you have banks of 10 output FETs per channel: “The reality is that substantially different transfer characteristics of so called ‘complementary devices’ especially power FETs, utterly overwhelm any attempts at symmetric behaviour”. Halcro will never condone poor behaviour. So, as Peter Foster emailed me:

It turns out, that if you tightly constrain the operating conditions in a specific way, these FETs can be made to work as almost perfectly linear devices. This is but one of a significant number of unique elements that distinguish a Halcro amplifier from conventional audio circuits.

Halcro’s overkill multiple protection circuitry is the stuff of legend. So forward-thinking, it’s been retained with few modifications in the Halcro Eclipse Stereo power amplifier. Like what I see as being Candy’s target-specific approach to distortion/s, I understand there are dozens of different types of precision “calculating circuits” which constantly monitor various critical functions of the Halcro amplifier. They regulate the apparatus with more normalising gaze, power and discipline than the philosopher Michel Foucault could ever muster. This mini-audio diagnostic panopticon covers, but is not limited to, output transistor protection as described above, DC offset protection, transient mains overload protection, input overload protection, and amplifier inter-stage protection. The mini-Halcro Department of Corrections, further, ensures that not only is the amplifier short-circuit-proof but has current limiting for the output stage as well as for the power supply and will cut out if some of the most common faults are detected in the power supply (such as over-voltage, the master clock running at an incorrect frequency, or at excessive temperatures). The old dms had gradual power limiting if the amplifier became too hot, but Lance Hewitt, now Major Longwood, told me:

The over-temperature protection turns the Eclipse back to standby, not reduce the output. The 58/68/78 did that, but it introduced so much distortion that it defeated the purpose of the amp and created a very expensive heater.

“Switch it off, switch it off, switch, switch it off, switch it off/Protection” sings Graham Parker and the Rumour. With Squeezing out Sparks in my head, I asked Hewitt whether all this over-protection might kill the sound of the amplifier in some way during playback.

No. The protection in Halcro amplifiers is specifically designed not to interfere with the audio until required. The protection circuits used in Halcro amplifiers monitor many parameters but take no action until pre-set levels are exceeded. For example, the output current sent to the loudspeaker is constantly monitored, but there is no constant feedback through the audio stage until the limit is exceeded. Once the limit is exceeded the protection circuit turns on and limits the output current. This can be heard in the loudspeaker output then, but not before the limit is reached.

When another company’s RFI-minimising product unwrapped itself from the power cord and, by an act of God, became wedged in the power outlet directly driving the Halcro amplifier, it tripped the entire AC to my apartment. The Halcro powered down with preternatural calm. And, started up again without skipping a beat. I, on the other hand, almost electrocuted myself. But then I am not a Halcro.

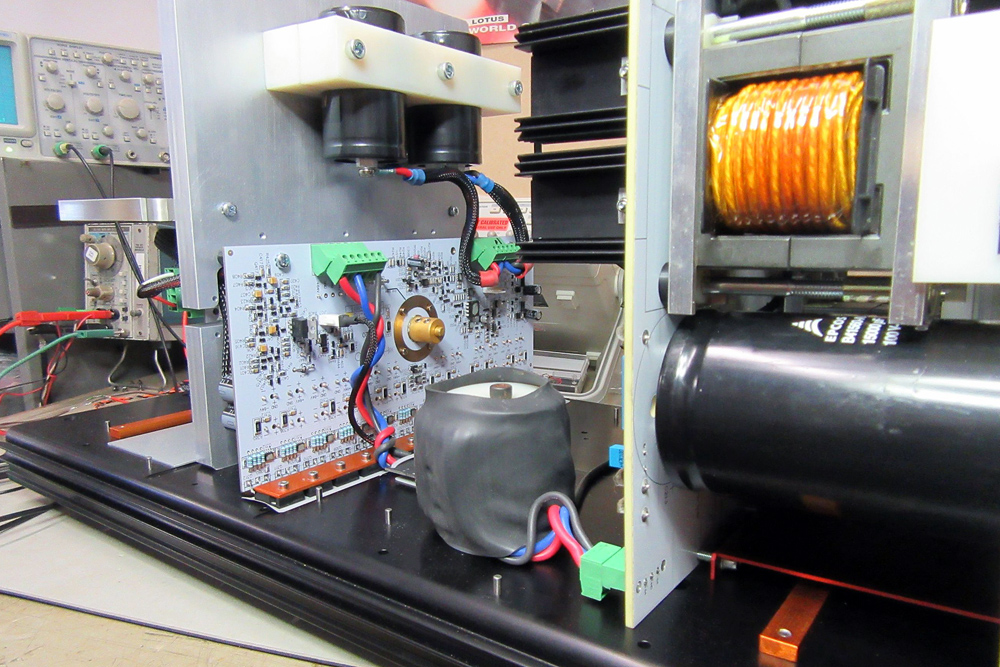

Audio Power PCB showing large shielding block between it and the Audio Input PCB

Audio Power PCB showing large shielding block between it and the Audio Input PCB

Other distinctive technical innovations carried over from the Candy-era in the Halcro Eclipse Stereo power amplifier – and all obviously geared conceptually towards the D-word, Candy’s desideratum – include custom made litz-wired transformers and inductors in the power supplies and the very unusual K. Curvecock-sized gold-plated solid copper coaxial transmission line er, pipe, which connects the input stage to the output stage. Inside this wound copper tube is a spiral-shaped 6 mm gold-plated copper conductor rod which also serves an output coil to prevent oscillation distortion in the output signal and a Teflon insulator. The chunky gold loudspeaker terminals are connected directly to an extension of this pipe which works to lower inductance. The extremely low output impedance of the Halcro amplifier makes it compatible with a broader range of loudspeakers, totally unphased by a loudspeaker’s changing impedance with frequency.

The genius output stage is housed (and physically isolated) in separate, heavily shielded chambers with one stereo channel in each of the vertical towers or ‘wings’ of the Halcro’s iconic ‘big H’ shaped enclosure. The towers or ‘wings’ also act as the finned heatsinks for the amplifier. The high-current output stage is separated from the input stage by a substantial eddy current screen so that any non-linear effects generated by magnetic noise coupling of the V-FETs are isolated from the input stage. Candy emphasises that: “It would be impossible to achieve the very, very low distortion without this feature”. Indeed, substantial eddy current and electrostatic shielding is used throughout the design to reduce magnetic interference and lower distortion. Very expensive six-layer printed circuit boards are used in the amplification stage to provide further isolation and shielding. This is said to “lower high-end THD” and up bandwidth and stability, as well as to minimise stray magnetic fields and to accurately define earth and voltage references etc. The power supply section gets four-layer PCBs to minimize voltage spikes and E.M.I. (and “A & M”…) to improve power supply efficiency and reliability. I’ll come back to the vertical, sectional (not modular) chassis design because this is one of the areas where the Longwoods have made musically significant improvements.

Mathematically precise…

The Halcro Eclipse Stereo power amplifier pretty much emulates the circuit in the Eclipse Monoblocks but is scaled down in absolute power terms because of its shared power supply and reduced surface area heatsink-wise. It also loses the current loop input of the Monos and the capacity for universal mains operation. Power output for the Stereo model is rated at 180 watts into 8 ohms and 350 watts into 4 ohms (with both channels driven, measured at 1kHz, and tested as continuous not peak rated power) compared to 250 watts into 8 ohms and 450 watts into 4 ohms for the Monos. Although on paper this looks identical with the numbers for the dm 38, Peter Foster would have you know that “the Eclipse Stereo is designed to operate at higher voltage and therefore much higher output power than the dm 38 because it sounds better so that’s how we now configure them”. To underscore the fact once more that the Halcro amplifier has zero recourse to excessive negative feedback, its recovery from “hard overload” again measured at 20 kHz into 4 ohms is a mere 1 ms.

For those with super hearing, the Halcro Eclipse Stereo amplifier has an extremely wide frequency bandwidth. Its frequency response is claimed to be only -3dB down at a very high frequency point of 215 kHz (3 Hz – 215 kHz, measured at an output of 1 watt) and is -1dB down at 90 kHz (7 Hz – 90 kHz, again at 1 watt). As previously mentioned, the Halcro also has a very low output impedance and remains stable not just under a demanding loudspeaker load but completely independent of load. Mike Kirkham claims: “It’s the only amplifier that will measure identically regardless of load”. The three input options on the rear are an unbalanced voltage mode (RCA) input with a stated impedance of 22 kohms; a balanced voltage mode input of again 22 kohms + 22 kohms and, premiering for the first time ever in a Halcro stereo model, a ‘minimal path’ voltage mode RCA taken from the Monos which has an input impedance of 660 ohms. The latter sidesteps a gain stage (the input buffer) and as a result inverts absolute polarity. This ‘minimal path’ input was added because Kirkham advances “it sounds too good not to incorporate in the Stereo amplifier as well”. The relatively high input impedance of the Halcro amplifier means it will get along just fine with a wide range of preamplifiers including many lower output valve-driven ones. The Eclipse Stereo is one fast mother (of invention) with a maximum slew rate for both small signal and maximum output voltage of 100V/ms.

And now the envelope please… For the numbers you’ve all been waiting for… The clear winner, with Total Harmonic Distortion of less than 1000 parts per billion at full power, is the Halcro Eclipse Stereo amplifier. Measured at 1 kHz THD is less than -120 dB up to 20 kHz at 350 watts into 4 ohms. The ‘mathematically precise’ amongst you will note that this is a total technical knockout over the “less than 3000 parts per billion at full power, immeasurable at normal listening levels” THD measurements of the already Twiggy-like dm 38 stereo amplifier of the Candy-era. (Phew. I’ll just sprinkle some Tassie small batch on my 3 am cornflakes and continue…).

In all my years following Halcro’s progress, I don’t think I’ve ever once read that Bruce Candy didn’t ultimately use his ears to develop and refine his distinguished creations. Halcro was brought into existence and pushed the boundaries of what’s possible in amplifier technology wholly in the service of music, not merely to challenge the theoretical limit of Audio Precision test equipment by means of test tones alone. The new Halcro team said of the new Halcro Eclipse Stereo power amplifier:

It must measure well. That’s a given for Halcro but that’s just the start. Immeasurable distortion and phase accuracy are the key drivers but really, the only thing that matters is how engaging it is musically. That is the goal. Realisation is an obsession with detail – detail that most amplifier designers aren’t even aware of because only the Halcro design exposes them.

Since the Longwoods acquired Halcro in 2014, they have explored every aspect of the unique design for possible improvement – and possibly earning themselves their own diagnosis in the DSM-5 in the process. Having Lance Hewitt on board for the second coming is, of course, an untold boon. He’s worked on the Halcro platform with Bruce Candy from before Day 1 and knows every nook and cranny of every iteration of the design.

Consider the improvements made to the distinctive, vertical chassis constructed in the shape of the letter H which Australian turntable manufacturer Mark Doehmann remarked to the author is “the Sydney Opera House of amplifier design”. In 2002, the instantly recognisable Halcro silhouette whose aesthetic could have been lifted straight off the deck of the Starship Enterprise (NextGen) won an industrial design award from the Chicago Athenaeum Museum of Architecture and Design. Apart from being bloody big and really bloody heavy (62 kg!), the Halcro edifice is not just a pretty façade – or H-sized act of towering hubris. It is instead the ultimate architectonic expression of form following function.

Power supplies and output sections are inherently “A Noisy Place” to invoke “the sidewalk doctor”, “the Devil’s son-in-law”, the great Jamaican DeeJay I-Roy. Thinking outside the (single) box, Halcro has physically quarantined the various amplifier elements or stages into a number of completely separate, heavily shielded compartments comprising the H structure. The power supply stage occupies the whole of the bottom box. The top box is split into multiple compartments shielded internally by up to 1.5 mm aluminium plate. In the top box there is the power output stage at the bottom, then above that is the input stage and sitting next to the input stage, but shielded in its own sub-compartment by a 0.9 mm thick copper wall, is the ‘coily cable’ output filter/inductor stage. The new owners have implemented much better shielding between the various circuit elements and in and around the most sensitive circuits of those elements. The Longwoods have also changed the interconnections, the wiring looms and connectors etc., between the circuit elements to further reduce non-linear effects. The dm 38 had three main compartments. According to Peter Foster, as a result of the added shielding, the Eclipse Stereo now has…

Four main chambers - power supply, input stage (left), input stage (right) and power stage – although within these four main chambers there are a series of heavily shielded sections that protect delicate input circuitry further so you could almost say that there are six chambers.

The casing itself has been completely redesigned. The satin silver anodised casework of the old dm series tended to ring like an Adelaide church bell. The new Halcro Eclipse casework is machined-from-solid and each chamber or compartment is now fabricated from up to 10mm thick folded aluminium. The substantially thicker casing provides greater rigidity which “all but eliminates the microphonic effects of airborne vibrations”. The winged uprights are also much better damped. The joins connecting the horizontal chambers to the wing sections are strengthened to better seal the chambers from the outside world as well as to reduce the effect of mechanical resonances from within. Even though you can’t tell, Foster explains:

The wings are actually screwed to the horizontal chambers. Halcro went to such extraordinary lengths with the original design to retain sculptural form that the mandate was “there must be no visible screws anywhere that detract from the sculpture”. We are following the mantra with future designs.

The striking new finish of the Halcro Eclipse Stereo amplifier is as robust and durable as it is attractive. As if to highlight its updated sex appeal, the H-shape – the shapely H? – has now grown some curves. The stroke me please coat makeover is wet sprayed with layer upon layer of aerospace-grade paint giving it a glowing, pearlescent appearance redolent of Apple’s metallic space grey colour. It’s one seriously expensive process. The customary wooden feet or plinths ain’t cheap to make either, being hand carved from solid wood by a local guitar luthier. Mahogany is standard (recessed for spikes) or, as in my review sample, uprated high-density Australian Redgum – 130 year old recycled farm fence posts to be exact. Every Halcro amplifier is individually handcrafted in Adelaide with artisanal care and attention to detail: “Every board receives the human touch. Every element hand tested. Every panel is hand finished”. It goes without saying that every amp is not only measured but checked by a human ear before it goes out the door of the brand new purpose-built Halcro factory.

Over the many years of critical listening component selection became an obsessional focus for the Longwoods. As they wrote me:

When you are dealing with a system that creates negligible distortion, each component can make a significant impact. Two components that have the same nominal specifications do not necessarily behave the same way in these circuits. They can have a dramatic impact on the performance of such a finely-tuned circuit.

In the new Eclipse Stereo, taking advantage of Lance Hewitt’s vast experience in printed circuit board design for Minelab as well as for Halcro, systematic improvements have been made to the circuit topology of the amplifier input and output boards. This includes subtle changes in how the tracks have been laid out as well as changes in ground plane segmentation resulting in PCBs with much shorter and quieter signal paths. No stone was left unturned right down to moving some components closer to or farther away from others for minimum non-linearity and maximum musical gain. It wouldn’t be a Halcro, of course, unless most of these key implementations did not remain as closely guarded a secret as the recipe for Vegemite: “so much so that semiconductor part numbers are engraved off and then the sensitive circuits are buried under a layer of opaque epoxy”. Knowing these guys as I do, they would have listened to the sound of the epoxy too.

When subjected to rigorous cross-examination not one Longwood cracked even under sustained pressure to give up their trade secrets. What we do know is that Halcro has always used industrial grade as opposed to mere commercial grade semiconductors for enhanced reliability and stability. It uses only highly linear resistors and highly spec’d MKP10/FKP1 capacitors in the critical audio signal path. All electrolytic storage caps in both the amplifier and power supply stages are rated to a sweltering 105 degrees to ensure extended operational life. I’m now also reliably informed, “there have been changes in the size and distribution of energy storage capacitors which has allowed us to provide more dynamics”. Still, that exceptionally rigorous discipline over the Halcro circuit remains ‘a constant’. Components such as semiconductors, no matter how new and improved, no matter how hush-hush, will always have intrinsic non-linear effects because characteristics like capacitance, gain and frequency will always vary with voltage and current. Halcro reigns supreme when it comes to dealing with the distortion/s arising. It has long had the proprietary know-how to ensure that, as Candy says, the voltage across and the current through semiconductors is kept under “very constant conditions”, thereby “almost eliminating such effects”. As with its crossed-over output trans-sistors. Or, as the other (Velvet Underground) “Candy Says”: “Doo doo wah”!

You would be wrong to think that the listening-first re-engineering imperatives of the new Halcro team involved only an exhaustive process of component switcheroo. Kirkham points out that the Longwoods hold four patents already on the new Eclipse technology and that some top-secret revisions to the ground-breaking Halcro dual switch-mode supply is one of their own. The revolutionary Halcro power supply architecture contributes in no small measure to the ultimate success of the circuit. Back then a switch-mode power supply was a dirty word. But the technology has been transformed by the progressive company to banish mains generated harmonic distortion and to show the competition a clean pair of heels in terms of slew and refresh rates. The Halcro has a refresh rate, for instance, “which is 1/115,000 of a second compared with a standard peak rectified power supply that refreshes every 1/100th of a second”. That’s right, it ain’t got no “power supply rail droop”…

The first of the two cascaded power supplies is used for active power factor correction. Whereas a bog-standard toroidal supply distorts the AC being drawn from the mains with peak surges and idle lows, the Halcro’s unique PFC supply takes advantage of sophisticated active filtering techniques (series and common mode EMI filtering as well as high frequency filtering) to balance the incoming current and voltage waveforms so that they are identical and always in phase. The second power supply then takes the ultra-high quality DC generated by the first to feed the rest of the circuit with pure and stable noise-free lifeblood. The body of the Halcro circuit “and all that it requires in this world” (thanks Candy) consequently performs super-efficiently and super-quietly. Switching frequency is well outside the audible range except possibly for the super ears of B.C. himself.

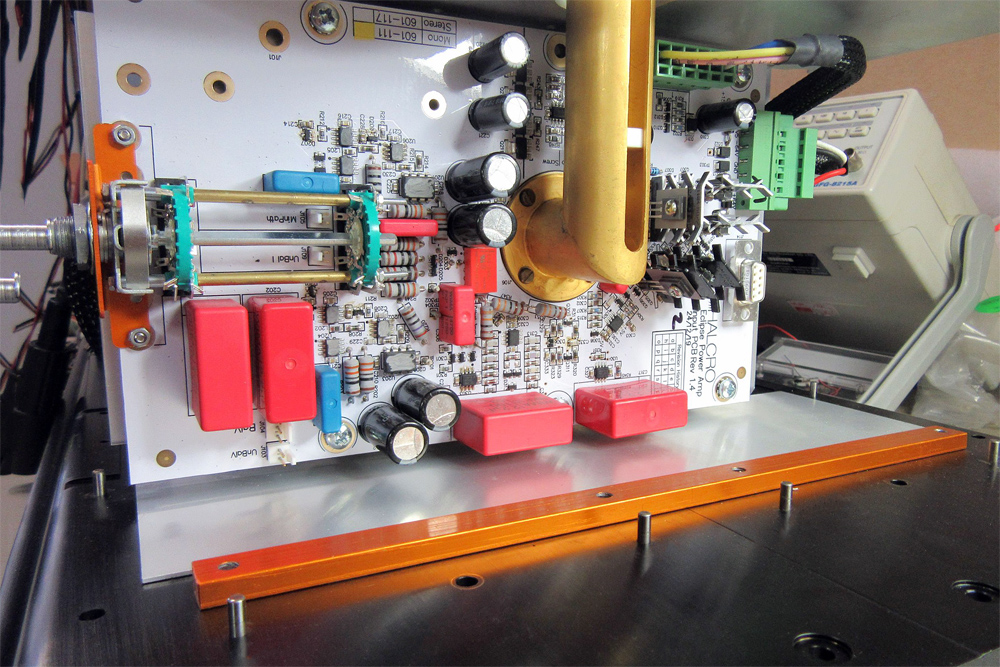

Audio Input PCB

Audio Input PCB

Meanwhile, back in the mathemagic – jungle. Arguably, the most critical, dare I say it, revolutionary innovation made by the Longwoods is to the Eclipse Stereo amplifier’s input stage. Apparently, the entire circuit is “brand new” and has “much higher bandwidth and lower distortion”. They claim it utilises “a completely different amplifier technology” but, true to type, they would not elaborate further other than to intimate that “it took many iterations to get this to work in the first place and then it underwent a methodical process of refinement”. All I could prise out of Mike Kirkham was the following:

Yes, the output stage is genius but the Halcro amplifier is a true ‘system’. Each element needs to work synergistically with all the others. In fact, take away just one of the ingredients and you don’t just lose a little bit of performance, it drops significantly. The amp becomes only significantly better than all other amps (rather than on a different plane). We actually reviewed all the elements of the design. We also knew that some of the biggest gains were to be found in the input circuit thanks to a few suggestions from Bruce – technology change driven by improvements in available semiconductors…”

So that’s why the three input options on the rear of the Halcro Eclipse Stereo amplifier, selectable by way of a big rubber rotary knob, have slightly lower input impedance specs ‘across the board/s’, Lance says, than the pre-dm 88’s. More importantly, it accounts for the indispensable addition of the “brand new” minimal path input option on the Stereo model. In certain contexts, this is the most musically transformative selector of all.

They Speak of Many Things

Meanwhile, back in Adelaide. Meet the Longwoods (for an earlier perspective hit the link to the SoundStage! Talks video with Edgar Kramer and the Longwood team):

Peter Katsoolis: What induced you to resurrect the brand? (What on earth were you thinking?)

Mike Kirkham: I was helping a friend out one Saturday morning at a record shop he owned in Stirling in the Adelaide Hills. In walked Lance Hewitt, whom I’d never met. Lance was introduced to me as the former tech guru for Halcro. I enquired as to what had become of this iconic Australian Hi-Fi company. Lance informed me that they had wound up operations and the company was effectively in limbo and that most of the stock, tooling and manufacturing equipment was being held in a massive storage facility in Port Adelaide. Lance also mentioned that the lease on the warehouse was about to expire and Bruce Candy and the other owners were looking for options.

I relayed this information to Peter Foster (my Magenta Audio business partner) and he promptly contacted the existing owners. The brand had effectively been put into mothballs, but Peter managed to negotiate an arrangement whereby our new company Longwood Audio would purchase all of the assets, brand, stock and IP. The deal was done in April of 2014. The brand was too good to let go.

PK: How did you get Lance Hewitt back on board and what is his role in the new company? What experience did he bring from the old Halcro company? What is yours and Peter’s?

MK: Upon acquisition of Halcro, Peter and I knew we could not progress without Lance’s knowledge and input. Lance knows everything there is to know about the products. We therefore gave Lance a third ownership of the business and locked him in a room to begin working on new designs.

Peter Foster is a laser physicist and brings a wealth of engineering and electronics knowledge to the company. I’m the incredibly annoying ears of Halcro [PK: and an accomplished musician, author and studio owner].

PK: What are the principle design goals/imperatives for the new Eclipses?

MK: Pure emotional expression of music. Impeccable measurements are just the launch pad.

PK: Can you elaborate on what you mean by “phase coherence” in an amplifier and in a system – can it be measured in an amplifier?

Lance Hewitt: Phase distortion (otherwise known as a delay distortion) occurs due to a range of reasons, including non-linearities which result in a variation in the time it takes for an input signal to appear at the output. A variation in the propagation time through the amplifier. As the signal passes through the amplifier this propagation time will depend on a range of factors including the topology, the types of semiconductors chosen, the biasing… and it will generally increase progressively with frequency. Another factor that effects propagation time is the amplifier’s frequency response.

Consider an extreme example to demonstrate the point. Two notes of vastly different frequencies are played at exactly the same time. If the first note sits right in the middle of the amplifier’s frequency response it will be amplified as expected. If the second note sits right at the extreme of the frequency response then the amplifier will be limited in how quickly it can respond to the input. This results in a slower than expected rise time for the second signal. Effectively a delay compared to the first signal. This is an extreme example, but the same is true for any variation in the gain with frequency. There are many ways that different components of a signal can be shifted relative to one another. These also change the timbre of an instrument, that unique voice or texture created by its harmonic structure.

In a musical sense then, phase is the ability of an amplifier to maintain the temporal relationships of notes in complex music. Time delays destroy the critical pitch relationships that are so important to musical expression. They also move the apparent position of the sound within the soundstage. Varying phase relationships cause instruments, voices and even single notes to move within the soundstage.

PK: This generation of Halcro is described as being more “musical” than the previous series. What does this mean in terms of the design approach and how (and what) we hear?

Peter Foster: I think we have improved on both. In physics, energy can neither be created nor destroyed. It simply changes form. In audio, music can’t be created by a component but it can be destroyed. You can’t create an engaging musical performance from nothing. How does the amplifier know what to add or subtract from a dull signal to make it musical? If you take an amplifier that is already extremely accurate, the only way to make it more musical is to make it more accurate. By contrast, if you’ve got an amplifier that has significant shortcomings then you can compensate for that by voicing it in a way that sounds more pleasing, but all you are doing is making it less bad. So if you come from the premise that it is already exceptional then the only way to make it more musical is to make it deliver an even more faithful representation the input signal.

In terms of design approach, we aim to make the most accurate amplifier possible – negligible amplitude distortion, frequency distortion, phase distortion, crossover distortion and intermodulation distortion. We improve every element of the design from a technical standpoint and then tweak the final implementation by ear. The result? Music, pure and simple.

PK: What is the point of ultra-low distortion in playback when the distortion in the recording, that is, the studio and the whole process of recording the musical signal is many, many magnitudes higher?

MK: Distortion is part of the recording process. In fact, musicians are specifically looking to add certain types of distortion or colouration to create the sound they want. Some of the most revered microphones and even mixing consoles are quite coloured. Our objective is not to minimise distortion for the sake of minimising distortion. Our aim is to create the most musical and faithful representation of what the artist recorded. Add nothing, take nothing away from the music. It just happens that the only way to avoid adding ghost notes, colouration, phase errors is to avoid distortion in playback.

Kirkham also happened to be the guitar tech for Guided by Voices the last time they hit Adelaide. “Are you amplified to rock” proud brothers and sisters? With the Halcro Eclipse Stereo in play, the club is very much open.

The Tone Scientists

Despite all the technocratic complexity, the Halcro Eclipse Stereo amplifier sounds like no amplifier you’ve n-/ever heard. Nor does it sound entirely like a Halcro of old. There is still that trademark Halcro speed and astonishing clarity and purity. There is still that insane resolution and explosive dynamic snap: micro-, macro-, and all points between. It has the unmistakeable ease and effortless see-through, hear-through, sense of absolute fidelity to the source. It has that mind-blowing transparency, this uniquely transfixing Halcro transparency, which leaves even a seasoned listener slack-jawed and rooted to the spot with sandwich dropped. The hallmark disappearing act pulled by a Halcro amplifier remains revolutionary. It’s like you’re hearing no amplifier at all. There is simply nothing between you and the music. It’s quite the trip.

The Eclipse Stereo gives up none of the traditional Halcro virtues. But the new amplifier gives a whole lot more enchilada in terms of musical persuasion, engagement and outright satisfaction. To these guttersnipe ears, even the most impressive Halcro amplifiers of yore could sound too lab coat, particularly in the wrong system, and a tad lean and harmonically threadbare. Lamentably, this is the accepted sound of so much extreme high-end audio even today. All that glitz to get no soul. Now, the Eclipse series has persuasively and seductively redressed the balance. Tonally as well as musically, you get more animal, less audiophile machine. Now, there is not just a sense of correctness but also a sense of rightness. It’s as if, as Lou Reed might say, the Eclipse Stereo is drawing new musical and emotional life from electricity that comes from other planets rather than your grotty home AC. It’s as if the new owners spent quality time with Swedish anarcho-punks Refused and discovered the “Liberation Frequency” of musical reproduction, the alchemical “sounds of liberation”, not by adding “New Noise” but by removing even more of it.

Over every conceivable sonic parameter the Halcro Eclipse Stereo amplifier exhibits a new freedom from sonic artifice and artefacts. Give it time/leave it on. Even from start-up its hits you on all cylinders: The complete absence of the usual electronic colourations that impede you from getting closer to the real thing. It feels like the usual sonic brake lines you’re used to hearing in high-end audio amplification have suddenly been cut. Yet, there is no loss of steering or organisation or control. The Halcro amplifier has evident authority, and is evidently ultra-clean sounding. But this is not the sound of transistorised sterility and restraint, or of stiff lip high-end polish and politesse. It can get down and dirty and dance the hard boogie exceptionally well when the music demands it.

Consider “Error in the Signals” by Napalm Death. This is a track of furious, raging sonic violence. Most extreme high-end audio amplifiers, no matter what their typological persuasion, render this extreme music somehow tamed, con-/strained, and anaemic. Through the Eclipse Stereo, it’s an appropriately grinding, lunging, and hair-raising ride. Even on the loudest, most unchained passages, there is no hardness or constriction or dynamic compression. Separation is breathtaking. The sonic chaos is tracked without confusion. Intelligibility and coherence are of the highest order. Transient response is startling, downright scary. The Halcro has boundless power reserves. It has superb, grapple-hold grip with absolutely no smearing or bloat or lag. Once again, the signal is freed from the apparatus. No matter how forceful the music, nothing sounds forced. Forget a lack of editorialising, here there is absolutely no censorship at all. From a sputter to an excoriating Barney Greenway napalm scream, the Eclipse is an open book musically – totally organic, non-mechanical and free-flowing. This is no lurching Frankenstein simulacrum of the real thing. The Halcro’s limitless power is deployed in the service of the beating heart of music, never for its chest-beating, power-crazed self alone.

I’m a hi-fi guttersnipe, Greek, punk and unloved (…), and I believe the privilege of enjoying expensive high-end audio should be a shared social experience. I believe that most of us crawled out from caves many thousands of years ago. For good reason, it was pretty hard to get power to Quad ESL-57s down there. I nonetheless had an unprecedented number of audio sophisticates over (stay) when the Halcro was in situ. Listener fatigue through the Eclipse Stereo was non-existent and listening sessions were limited only by the lateness of the hour, the last drop, and a last-minute concern for the neighbours. A repeat offender was Sir Les Davis of those stunningly effective eponymously named audio accessories. We spun “I’m Free” by The Who and Sir Les pronounced it the best he’d ever heard it. Ditto the MC5. Ditto Nick Drake’s Bryter Layter. Ditto Donny Hathaway’s Live. Any Freddy King on Federal. Pretty soon it became apparent that it would be impossible to isolate representative tracks for this review when everything we listened to was the definitive rendition of it. One night, we grooved on Tim Buckley’s Works in Progress, a long out of print CD on Rhino Handmade. The next day, Les called to say he was so blown away by what he’d heard he had immediately gone out and tracked down a copy. That’s what it’s all about isn’t it? Isn’t it?

Eclipse monos driving Duntech Audio Princess speakers in Hong Kong distributor’s showroom

Eclipse monos driving Duntech Audio Princess speakers in Hong Kong distributor’s showroom

Perhaps because the Halcro amplifier has that unique sub-noise floor thing going on, it wipes the floor on the competition when it comes to the glare- and glass-free enjoyment of ‘less than stellar’ recordings. Useful, given the majority of my most treasured music falls into this category. Take the incredible Distortions LP by The Litter. This is as pure and unbridled a slab of primal 1960s garage-psych longing as you’ll ever hear this side of a Pebbles compilation. It was recorded live to what? Four track? And the only studio adjournments were the fuzz guitar sounds that gave the album its title. Differentiation between tracks and indeed fuzzy textures is exemplary. No, the Eclipse Stereo won’t turn a VG+ recording into an M- . But somehow it just doesn’t matter anymore. The Halcro amplifier expands the conscious of the listener like the grooves of the record suddenly got way bigger. Tape hiss and noise are ghosted away as does the finest phono cartridge. Hot stuff that formerly frustrated and as sounding harsh and pinched on most high-end kit now sounds glorious and not at all strident, edgy or brittle. For example, Dylan’s harmonica on “that thin, wild Mercury sound” of Blonde on Blonde sounds glorious and not at all strident, edgy or brittle. Or Howlin’ Wolf on the bawling “Tired of Crying”, who around the same time in the late ‘60s was channelling Dylan (who was channelling Wolf). I was genuinely blown away. Your ears are constantly tantalised but your brain is idling and stoned-to-the-soul relaxed leading to always on (the money) listening sessions.

The Eclipse Stereo has timing to burn. In this crucial aspect, it is vastly improved over earlier iterations and I for one would buy the amplifier for this quality alone. My trusty Shun Mook loudspeakers usually motor like a big Californian V-8 but here they are transformed into boogie-woogie monsters of PRAT. I consulted Bill Ying of Shun Mook often during the course of this review and I remain grateful for his insightful wisdom and support throughout. No matter what speaker it was driving, the Halcro’s bass response (and resolution) was inevitably deep, punchy and extended. It may have the best pitch definition (and inner detail) I have ever encountered. Halcro bass is tight, and rhythmical but never uptight. Drop the needle on The Triffid’s swinging “Kelly’s Blues” and hear why Martyn Casey has been the engine room for the Bad Seeds ever since. Unlike most “big amp bass”, the Eclipse Stereo doesn’t sound unnaturally bloomy and big-bottomed. The Halcro’s nether regions are agile and extraordinarily expressive. The Halcro’s upper-bass transitions seamlessly into and allows the amplifiers’ wide open midrange to breathe, er… freely. Need another referral? Book an appointment with the effervescent, jump-start electric bass on The 5 Royales’ infectious “It Won’t Be Long aka Soul House” or the sliding-fluid, frictionless acoustic bass of Richard Davis on Kenny Dorham’s Trompeta Toccata. Then, of course, there is his prescriptive contributions to Astral Weeks.

Astral Weeks sounds f****** magnetic through the Eclipse Stereo. Van the Man uses his voice like a musical instrument on this largely acoustic based recording. Every subtle shift in his distance from the microphone is starkly revealed. Every micro-modulation in his phrasing and vocal projection is clearly audible. The amplifier gives full expression to the singer’s “Slip Slow Slider” vocalisations. Here they are delivered with the full range of articulable dynamic contrasts and pressure sensitive timbrel shadings. If this is phase coherence, then I need more. It affords the listener the complete magical mystery tour. The Halcro’s freakish transparency takes the listener to another realm spiritually and emotionally, giving full voice to the transcendental aspirations of the artist. Van Morrison put every sinew, sliver and shard of his being into this work as if his life depended on it. With the music mafia breathing down his neck at the time, it literally did. The Eclipse Stereo packs the full sucker-punch emotional wallop that I suspect the earlier dm series was never quite capable of attaining.

The Eclipse Stereo is rather obviously a very wide open bandwidth design. And resolutely linear from its bass deep underground to its stratospheric treble. The treble feels genuinely limitless in extension with, seriously, zero granulation. This leads to particularly impressive stereo depth perspectives. Layering in the soundfield is bounded only by the individual recording, the room and the rest of the system. Further, each layer in that soundfield has incredible depth in and of itself. It sounds notably focused and (phase) coherent off-axis. Once, I was at the other end of my apartment jumping around to Phaseshifter by Redd Kross when the music suddenly lost body. I raced back to the system only to find that the LED readout on the valve preamplifier I was using was telling me I needed to replace a rectifier tube.

Transient reproduction, I’m tempted to say enunciation, is as fast as life itself and as wholly developed as I have yet experienced. Listen to the interplay of the various stringed instruments on Haydn’s playful Sun Quartets Op 20 No.s 1-3. Transients manifest instantaneously with jump-out-of-your skin startle and tail into an infinity as black as Queen Nefertiti’s eyeliner. The purity of the Halcro amplifier’s transient resolution leads to far more realistic reproduction of harmonic overtones. It excites the senses. It also offers a very real sense of the spaces between notes, between instruments, and between recorded spaces. Those spaces are not the sonic wormholes of digital emptiness. Rather, they are the living, breathing organic spaces that inform and are informed by actual music-making.

Freddie Hubbard’s first date as a leader, Open Sesame, is one of the best Bluenotes for conveying a palpable sense of a natural acoustic space. Through the Eclipse Stereo the recording is sonic dynamite. In performance, both Hubbard and saxophonist Tina Brooks get big-bodied tone out of their respective instruments with notable size, scale and bounce. Yet, each instrument is correctly proportioned in terms of physical size and scale – and bounce. Reproduction of natural echo in a recording and maximal resolution of ambient cues is as good as it gets. Imaging is stable and rooted to the very spot where the performer actually stood. You are never hit by an artificial wall of sound with different instruments of different acoustic proportions coming at you all at once on the same audio plane (crash). Just as importantly, on McCoy Tyner’s piano keyboard, you can easily hear that pitch relationships are correctly spaced along the musical scale, neither flattened nor sharpened. The vanishingly low distortion and total exorcism of ghost notes via the Halcro amplifier means that instruments sound totally pitch accurate – and all the more tonally accurate and ‘first-date’ alive because of it. Trust me, you can reliably tune a real instrument to the right track. I suspect that, as John Atkinson once observed in his review of Vivid G3 loudspeakers, the Halcro’s uniquely tuneful presentation comes from a (note-) worthy absence of pitch-related distortion leading to far greater differentiation of musical pitches. Correctness rules – and correctness rocks.

You haven’t lived the audio life until you experience the Eclipse Stereo’s alluring and informative midrange performance. It’s not just wide open and teeming with information, it is surprisingly lyrical and liquid. Through the Eclipse Stereo you can analyse the smallest detail to your heart’s desire but you can also now dance around the room while doing it. You can peer into the darkest recesses of the recorded space with incomparable illumination and insight. But turn your back on the system and you are literally on stage with the performers. It’s an exhilarating, mind-altering experience and one that I have never before so palpably and physically encountered in all my years listening to high-end audio. The EL34-based VTL MB-185 Series III monos are more forward and have larger, more panoramic imaging. They have that tube push with greater bass drive and rhythmic propulsion. The hybrid Robert Koda K-70s have more technicolour tonal exposition and contrast. Tellingly, neither amplifier sounds quite as at home driving the 97dB efficient Koechel horns as the invisible Halcro Eclipse Stereo. The “best amplifier in the world”? It just got better.

Architects of Planes of Discipline – Conclusion

It is a truth universally acknowledged (well almost) that fine measuring, technically perfect amplifiers do not necessarily sound that crash-hot musically. Fortunately, the new Halcro Eclipse Stereo power amplifier is a shit-hot music maker. Like the musical space-trekker Sun Ra who offered the poem that gave this review its subheadings, Halcro has imposed the ultimate technocratic discipline on its rather unusual circuit to achieve the ultimate liberation of the musical signal. The Eclipse Stereo embraces the “Two Worlds” so successfully Sun Ra would have taken this amplifier to Saturn, were he still earthbound.

I have dwelt too long perhaps on the technical aspects of the Halcro Eclipse Stereo power amplifier. But I loved the sound so much and it sounded so different to everything else out there – including its Halcro forbears – that I had to get to the bottom of why. My digging soon revealed a lot of mis- and disinformation had piled up around these self-styled “Architects of Sound” since the last time a Halcro amplifier graced this troubled planet.

In operation, the Eclipse Stereo is as silent as a Benedictine monk riding a half-pipe on the finest Spitfire wheels. Reproduction of every deep sinew of detail is bedazzling. The amplifier’s discrimination of transients inspires awe. The Halcro also has the most supple timing this side of the now immortal Charlie Watts, especially on the new minimal path input. The Eclipse Monos with their separate power supplies, infinite channel separation and extra storage capacitance must be truly terrifying. The fact that this is only Halcro Eclipse Season One comprehensively shakes my audio firmament.

In-situ at Peter Katsoolis’ listening studio

In-situ at Peter Katsoolis’ listening studio

The Eclipse Stereo amplifier’s out of this world resolving power does indeed attest to its vanishingly low noise floor. It’s a testament to its transparent and distortion-free character – although ‘character’ is devilish lexicon to use in all the circumstances here. But the new amplifier ain’t called the Eclipse for nothing. One breakthrough quality (and there are many) is that the Eclipse Stereo never leaves the body of music sounding other-worldly and not quite there in terms of texture and tone. A thing for the head alone. You will rediscover the four corners of your music collection like you’re looking for a kiss on a first date. But you will also rediscover yourself and what it means to be a listener again and again. That’s what this amplifier is all about. And why it means so much to me. Big ears strikes again.

With demand so outstripping supply, the new owners still have some wrinkles in the space/time continuum to sort out. Does it sound like a 300B amplifier as I’ve already read somewhere else? No. The Halcro Eclipse Stereo power amplifier is in its own orbit. It sounds like the most neutral, uncoloured high efficiency loudspeaker you’ve ever heard: Totally free. There’s the rest. There’s daylight. And then there’s Halcro.

…Peter Katsoolis

Associated Equipment

- Speakers – Shun Mook Audio Bella Voce; Koechel K-300 horns; SerhanSwift Mu2 Timber SE with Solidsteel SS-6 stands and prototype Mu3 floorstanders

- Amplifier – VTL MB-185 Signature Series III; Robert Koda Takumi K-70; Wavelength Audio Napoleon 300B monoblocks; First Watt SIT-3; 47 Laboratory 4706 Gaincard; 1974 Hiwatt four-hole DR504

- Preamplifier – Jeff Rowland Design Group Capri S2-SC with HP card; Robert Koda Takumi K-10

- Phono preamplifier – Boulder 508; CAT SL1 (phono stage only)

- Sources – Aqua Acoustic Quality La Diva CD transport and Formula xHD DAC; Simon Yorke Designs S9 Record Player with Shun Mook Audio Reference 3 cartridge

- Cables – Shun Mook Audio loom; Sablon Audio Ethernet and 75 ohm BNC; Luna Cables Orange AC and Skogrand Cables Wagner AC power cables; CFM Resonant AOS+3 speaker cable

- Equipment Support – Silent Running Audio Scuttle Mk2; Shun Mook Audio platforms; old skool Mana Acoustics

- Accessories – A panoply of Shun Mook Audio; a constellation of Nordost QRT and Sort; celestial Les Davis Audio; SPEC Corp. RSP-AZ1 Real Sound Processor; Arya Audio Labs RevOpod Dampers

Halcro Eclipse Stereo Power Amplifier

Price: AU$59,995

Warranty: Seven Years

Australian Distribution: Halcro

Carey Gully

South Australia 5144

+61 8 8390 1673

www.halcro.com